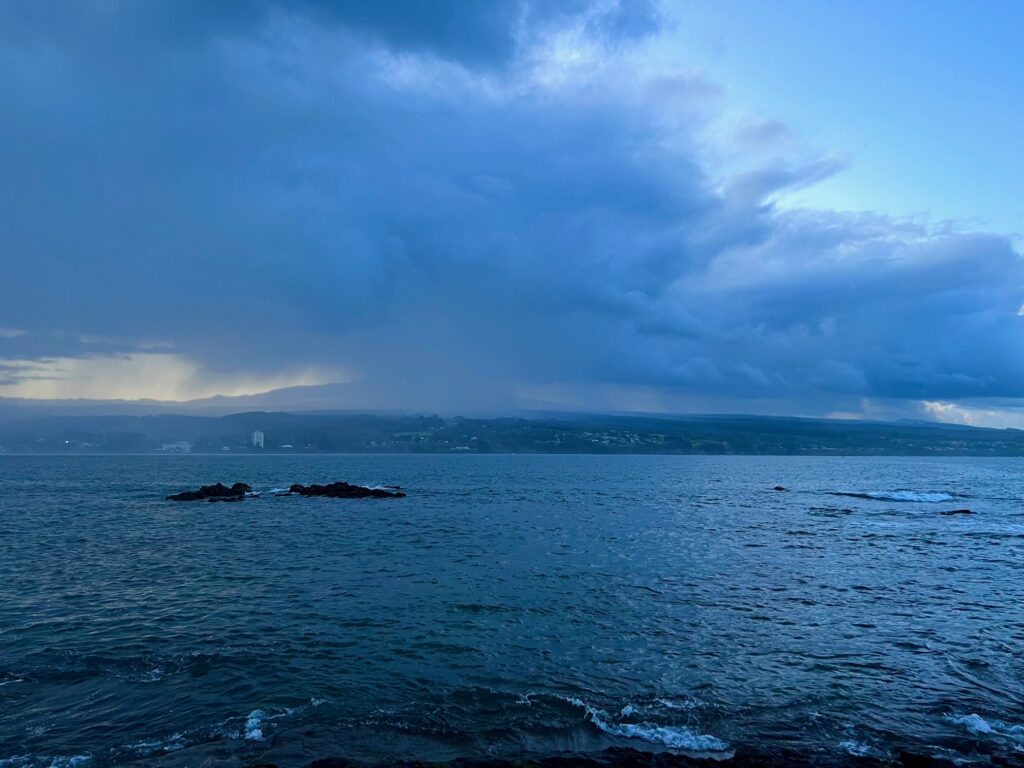

Hilo bay

November 14, 2023

The Hawaiian Islands, tucked away in the central Pacific Ocean, call to mind year-round sunshine, gorgeous white-sand beaches, and an iconic brand of global tourism. The fleeting few days of paradise amidst the daily grind of life can range from free campsites to resort hotels and secluded, thatched-roof bungalows charging thousands of dollars per night.

Last summer, my family and I left our Manhattan apartment to live in Hilo, Hawaii—not as tourists, but as transplants working in government-funded rural healthcare. The Big Island, a byproduct of volcanic activity, is the most isolated inhabited landmass in the world. We had stepped into a distinct ecosystem–one of stunning natural beauty, but also seeped in the habits of decades past and mostly devoid of frequent tourism. It was possible to trawl through the muddy trails and water and black-rock shores of this village and often feel, as Mark Twain had observed of Maui many years ago, “the spirit of its wildland solitudes…the splash of its brooks…the breath of flowers that perished some twenty years ago.” Hilo’s greatest atmospheric treasure is not sunshine but rather rain. It can arrive quietly, in small shivers of wet mist, or in fierce droves beating against all living beings, from silent seaside wrack to loud coqui frogs, drumming from the sky in serrated sheets that numb the mind into a meditative trance.

But the dark clouds hanging over Hilo, the rainiest city in the US, portend a feature of the Hawaiian Islands that is not often depicted in popular culture or in the media. In my first few weeks working as a gastroenterologist here, I diagnosed multiple intestinal cancers. Over the next months, my colleagues and I captured colorectal cancer in strikingly young patients—some were in their thirties, or even in their twenties, with no family history of cancer or other notable risk factors.

In April of this year, the National Cancer Institute revealed for the first time that young Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders (NHPI) between the ages of 20 and 49 experience the highest rates of death from any type of cancer when compared with other racial and ethnic groups of the same age, including American Indians, Alaskan natives, Asians, Blacks, Latinos and Whites. In addition to cancer, NHPI also suffer with the highest incidence of heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, and diabetes in comparison with all other ethnicities. They have among the shortest life expectancies in the country today. A variety of factors may be contributing to this phenomenon, including social, economic and environmental issues.

Disease is intimately linked to socioeconomic factors, and NHPI are more likely to live below the poverty level and to have higher rates of homelessness, unemployment, and imprisonment. Locals are faced with skyrocketing rents, flat wages, and inflated grocery bills. In addition, NHPI, with their unique sociopolitical history, have some of the highest healthcare needs but continue to experience barriers in access to healthcare. Until just a few years ago, the hospital I work for did not have a single employed gastroenterologist. Patients with certain gastrointestinal conditions—even urgent, life-threatening ones—would need to take the trouble to fly to another island. The physician shortage on the Big Island, which is profound and critical, extends across primary and specialty care of all kinds.

Environmental factors are also crucial to health promotion. We know today that inflammation, a primeval force meant to protect us, paradoxically plays a central part in all kinds of chronic diseases, including the conditions mentioned above. An anti-inflammatory lifestyle is essential to preventing or even treating chronic disease. Cancer is fueled by inflammation, which can affect all its life stages, from the initial genetic influences that transform normal cells into malignant ones to the continued growth and spread of cancer throughout the body. While genetic factors affect cancer incidence, recent research argues that early-onset cancer is a global epidemic that is largely related to diet, exercise and other lifestyle factors. A September 2022 study by researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston published in Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology states that cancer cases among those under 50, including breast, colon, esophagus, kidney, liver, and pancreatic cancer, have risen worldwide since around 1990, likely due to increasingly sedentary lifestyles and Western diets laden with processed foods, sugary beverages and alcohol use. The researchers point out that enhanced screening alone does not account for the noted increase in cancer incidence.

Ironically, Hawaiian residents at large have the longest life expectancy out of all 50 states. Year-round temperate weather encourages people to expose themselves to nature and exercise outdoors. Air quality, which studies show affects chronic disease and mortality, is among the cleanest in the country. And farmers markets with fresh, local and seasonal produce abound, boasting an array of salutary and exotic tropical foods. A traditional Hawaiian diet, in fact, is one of the healthiest diets in the world, and a return to this way of eating could have immeasurable benefits for all Hawaiians, including NHPI. This diet, which differs from the Westernized, “local” Hawaiian diet, predates the arrival of Europeans as well as East and Southeast Asian immigrants into Hawaii. It consists of indigenous foods as well as those introduced by the Polynesian explorers who became native Hawaiians.

Vegetables and fruits are centerpieces in a traditional Hawaiian diet, like the starchy taro root, its meat lightly fermented and pounded into creamy, pale purple poi, or its fleshy green leaves steamed into a luau. When I first came across a soup made of ‘ulu, or breadfruit, I tasted a strange and delicious hybrid of savory plantains mashed into fresh baked bread. All shades of sweet potatoes fill a traditional plate, as do edible ferns that grow in mossy wet forests. Animal foods, if eaten, are mostly lean and from the ocean, like raw cubes of simply marinated fish in a classic bowl of poke. And seaweed is a beloved condiment.

Small studies have shown that the traditional Hawaiian diet, which is mostly plant-based—around 80% carbohydrates, 10% protein, and 10% fat–lowers weight, blood pressure, cholesterol, and other markers related to disease. This diverse diet, which once allowed native Hawaiians to live off the land and ocean rather than imported food, may be the key to helping modern Hawaiians to reclaim their health, preventing chronic disease, disability and early death. Community-based, culturally-sensitive public health solutions that incorporate the traditional Hawaiian diet have found success, but such efforts must be implemented more broadly. Beneath the radiant allure of the Hawaiian Islands lies an unsettling world of health disparities that require urgent attention.